http://www.expressen.se/kultur/karin-olsson/radda-barnen-fran-kulturhatarna/

-

Är teatern farligare än verkligheten?

Minns någon fortfarande ”Bagare Bengtsson”-debatten?

Upprörda föräldrar ville förbjuda Lennart Helsings saga i slutet av sextiotalet. Rimmen var opassande och barnen kunde ta skada av den svarta humorn, menade man. Bagare Bengtsson var ju inbakad i en limpa …

I tider av stor och mörk oro svänger föräldraopinionerna gärna över till att begära kontroll, som om man kunde få bukt med verkligheten genom att förbjuda barnens böcker, pjäser och filmer. I Örebro har föräldrar och lärare – utan att se pjäsen – nyligen ställt in planerade lågstadieföreställningar av Mikael Cockes fina uppsättning av ”Medeas barn”.

När jag skapade ”Medeas barn” 1975 var det bland annat för att lätta på trycket för barn som upplever föräldrars skilsmässa som jordens undergång. Tillsammans med skådespelarna och Per Lysander testade jag sagan om Medea av Euripides i en lågstadieklass och barnen lekte fram scener där de funderade över vad en skilsmässa är. Vi reflekterade mycket över att sextio procent i klassen var barn till föräldrar som tillhörde den historiska generation som peakade i skilsmässostatistiken.

Tillsammans skapade vi en barnteatertragedi, men utan att den förtvivlade Medea dödar sina barn. De terapeuter och vuxna som handledde oss då beskrev vilka skuldkänslor barn har vid en skilsmässa. Barnen tar på sig skulden – det är mitt fel, tror de.

Vi bandade alla repetitioner med publik och fann att barnen skrattade – och att de vuxna grät. Det blev dock skandal, många ville stoppa pjäsen och förbjuda den – precis som vissa skolor nu har gjort i Örebro län. Vi lärde oss då att vuxenvärlden hellre hindrar upprörande berättelser med kritik av vuxna, än förändrar verkligheten för barn.

Tack vare öppna lärare och barnkunniga experter har pjäsen överlevt och sett scener och publiker på många håll i Europa och världen. I Frankrike är den en teaterklassiker och i Norge spelades den nyligen. Men varför vill vuxna hindra pjäser och barnfilmer? Vi hindrar ju inte barn från att leva i segregation, skilsmässor, alkoholism, krig, mobbning?

Tydligen behöver vi ta den vuxna, rädda människan ömt i handen och säga snällt och bestämt: Barn behöver starka berättelser om sanna saker, gjorda med kvalitet. I stället för att stoppa skolklasser från sådan teater, låt barnen tala, ta tid med dem, måla, prata om upplevelserna. Förändra verkligheten – censurera inte konsten.

http://www.dn.se/arkiv/dn-kultur/suzanne-osten-ar-teatern-farligare-an-verkligheten

-

laget

http://www.svd.se/suzanne-osten-om-svenskans-vackraste-ord/i/utvalt/om/svenskans-vackraste-ord

-

I have always asked my self – some main issues in English

When we who work with art for children and young people from around the world gather in the same room, I am always astonished, happy and impressed by all of our collective knowledge. We producers of art – from young to white-haired like me – we have, despite everything, been shaped by trying to describe for adults what we know about the ability of children to experience and use our art genre. At the same time, we have an enormous amount of knowledge about the powerlessness of children. We were also once children, and the price of growing up is to forget dependency and conquer the adult world in every way we can.

Many adults, with good intentions, want to keep children in ever-lasting entertainment to make them happy. However, we can recall that we searched for, well, the truth about how to live life, and that definitely did not exclude magic. On the contrary, we had fantastic solutions as children and, have we forgotten, we were obsessed with justice. We were also mighty indignant. We asked questions.

We, the white-haired who have spent time conducting research in the field “children and society,” we who have studied sociology, anthropology, theories of art, theories of play, psychoanalysis, the history of ideas, and new research in neuroscience, we are constantly searching for supporting arguments in dialog with the adult world that allocates, distributes and determines what children should see and be offered in the way of culture. We talk to each other, we teach, we meet patrons and politicians and civil servants, all the teachers and parents.

I have always asked myself, “Why is something that everyone agrees on so difficult to gain support for?” Namely that children are so important. Or that’s what we say at any rate.

Now that Sweden has adopted the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child as law, a milestone, it shall be a pleasure to argue for the rights of children to art and culture. An overall view of the state of the world, however, shows that it is difficult to argue for this artistic wonder that exists in our DNA; the right to express ourselves esthetically, to argue for art as a necessity, when we see the figures from UNICEF:

15 million children are caught up in war in violence.

The execution of children and attacks on schools are increasing. /UNICEF report /

Why does this contempt for children exist?

1

Childism: Confronting Prejudice Against Children, a book we should read and reflect over and spread

Childism is the collective concept the author and psychoanalyst Elisabeth Young-Bruehl uses in her book on child hate. The book shocked me with its clear-cut analytical position for the rights of the child. The author has conducted scathing interviews that illustrate the vulnerability of children in the adult parent sphere of power and influence, ”a prejudice against children on the ground of a belief that they are property and can (or even should) be controlled, enslaved, or removed to serve adult needs.”

This is a book with a passion for its subject matter, and “childism” is an excellent concept that I want to spread. The author writes that she searched a long time for a concept that would enable all of us to conceive of the discrimination that takes shape in the ignorance and violence experienced by children every day. I view the book as a tool fashioned from a humanistic approach based on facts. I discovered it at the Anna Freud Centre in London where pioneering research is conducted on the well-being of children and on treatment for children and their parents. Young-Bruehl writes, ” For childism is a societal phenomenon. Most individual parents, given the opportunity to be heard and supported, are not childist. They long to help their children, not merely control them. ”

2

”Warning to adults”

… the Art question: an artistic power for children is needed

I have written the above for those who will be reading, producing and financing my new feature film for children. The movie is based on my book and play Flickan, mamman och soporna (The Girl, The Mother and The Rubbish). It is about a girl who lives with her psychotic mother and her demons. We toured with the play for ten years. We performed it in European cities as well as in Johannesburg, Montreal and New York. The reactions in those cities were the same as the ones in Stockholm. And in each school class we met children with a similar experience; that of taking care of their parents. Adults reacted with grief, distress and abhorrence, while children, from seven years of age, were highly interested and empathetic and realistic.

To producers who fear the art criticism of the adult, I would like to say

Warning …

“You will want to save Ti and you will want to prevent children from seeing the love she has for her mother, who is in extreme distress. The girl, Ti, wants to save her mother, but there are demons that aim to separate the girl from her mother. Ti is faced with the overpowering task of outwitting powers that are invisible to her. But she can fight, and she has imagination, and out there, people are looking for her. Many children recognize this situation, however, we adults do not realize this since we are of the opinion that we have neatly arranged the world for them. A result of this attitude is that children live in a kind of chaos because we simply do not understand that they cannot foresee our actions. Don’t try to save children from seeing a film about a dramatic episode in the lives of a few people.

The movie is about portraying the viability of love in an unpredictable world. We have staged this story for ten years as a drama and have met children’s honest and direct appreciation, at the same time, we have also defied many adults.”

Childhood is a continuous here and now for children, and a child wonders about everything it sees, and a child sees the actions of adults in soap operas. And the child asks questions, and is given many strange, directly untruthful, digressive answers by adults.

Good drama, stories, are often those that speak the truth, in the opinion of us adults; truth in performance. This means nothing other than brilliantly acted and designed for the stage. Art requires funding to be able to process the drama for the stage and to make a deep, sharply dazzling impression. Quality costs. To pay salaries and hire those who are best for children has not become a tradition yet, but at Unga Klara I have insisted that no one shall be able to discern any difference in quality and immediacy between theater for adults and theater for children; both are equally important, equally entertaining, equally as deep. We work with the audience and language, and follow new developments in social research.

3

Baby Drama

New artistic research on children’s perception, why an esthetic sense of quality is an inborn need

To underline all this, the importance of art for a human being, I have shown my documentary film based on artistic research on how infants reacted to our play Baby Drama. I have not met one single person who is not touched by the filmed response of the children, aged from six months, to the grownup play about birth. During this research project I learned to reflect on the human innate need for theatre, because infants without previous theater-going knowledge sat as a theatre audience, collectively watching a play for one hour.

My theories are based on the existence of an absolute need in a child for gestures, faces, emotions, language and bodies to learn communication.

In the playful cabaret with six actors, the audience began to contemplate their own lived experiences. The close-ups in my documentary of an infant’s open vibrant face watching this performance is proof, yes, evidence of our adult significance as performers, as art distributors and proof of love for communication. Regardless if parents are a safe or an unsafe base, art is the exciting development of that base.

This year must be a better year for all.

(a shorter version is published in assitej world magazine april 15)

-

-Vad ska jag visa en liten?

Små och konst:

Babydrama , på min teater Unga klara 2004-5 var teater forskning för 6 månaders barn.

Jag ville se om en så ung publik kunde följa en pjäs och uppfatta att det var teater ?Kunde babyn ta till sig en konstupplevelse ?Det var konstnärlig forskning medan vi gjorde en föreställning och testade oss fram .Jag dokumenterade och intervjuade föräldrar och barnexperter med Ann- Sofie Barany ,barnanalytiker och dramatiker ,som skrev texten.Det formade sig till en studie av den unga publikens reaktioner-filmade med speciella kameror av Bengt Danneborn : de kom nära barnens reaktioner medan de upplever vuxna skådespelares rörelser dialog,musik. Vi vuxna var med om en överväldigande resa ; barnen svarade kroppsligt emotionellt starkt på föreställningen ,som var 1 timme och 20 minuter. Vi knäckte koden genom att inleda med 2o minuters kontakt och förspel där vi introducerade barnen i ”teater”: Vara med varandra, se skådespelare komma gå och försvinna..En tittut lek.8 månaders småbarn ser alla detaljer i en stor scenbild, vi kom att använde scenens alla möjligheter .Men vi släckte aldrig ljuset -då somnade vår publik.

Föräldrarna berördes djupt av barnens behov av estetik-teater.

Och vårt projekt att ta babyn på allvar fick rykte ute i världen..

Hur är det med film då för de riktigt små?

Som barnfilmsambassadör får jag frågor.

Ska en liten iöverhuvudtaget se film – ska en liten använda Ipad?

Jag får frågor som leder mig till tanken att är det verkligen film vi talar om-

Eller talar vi fostran, eller rädsla för nya media ? Eller,ja vad är kontakt med estetik.Är det nödvändigt?Hur länge får de hålla på?

Mycket litet är än så länge är forskat om bildens inverkan på små barn, Ja hur ska det se ut, en kontrollgrupp utan bilder – en som ” offras” i vetenskapens tjänst? Eller en som korvstoppas …. Men rapporter apporter kommer dagligen-på barns olikheter.

Lika många olikheter som familjer och individuella barn. Vad är grunden i en människa och hur använder vi fantasin för att förstå världen. Mänskligheten har alltid provat sig fram och format nya bildkulturer .Och barn med usla såväl som underbara föräldrar har hängivit sig åt egna fantasier och bilder.På min gata var alla barn utom jag förbjudna läsa serier på femtiotalet… Frågor kommer:

-Min lilla G ,barnbarnet ,han bläddrar på I -paden,det han vill se är mej,farmor, när jag dansar och så bläddrar han förbi allt och alla tills han kommer till bilder av sig själv, han ler och pekar på sig själv,utropar: Gustaf Gustaf Gustav.

-Min lilla dotter försökte öppna i Ipaden, som en handväska ,ville hon ta sig in?Eller fattade hon inte att den är yta med bilder.

De- i-pad flitiga bläddrarna är 1,5 eller yngre idag.Bästa barnvakten!Hur ska det kontrolleras.?

Eller vad är särskilt spännande?För barnen?

Jag själv rusade fram till bioduken och ville klappa en häst .Jag trodde den var verklig – detta var på min första biofilm.

Jag var tre..Vi vet att vuxna – i fimens allra första början – trodde att tåget som de såg komma rusande mot åskådarna ,skulle köra över dem , de kastade sig åt sidan.

Vi måste tydligen lära oss läsa bilden.

-Jamen. Hur mycket film ?

Diskussionen kommer fortsätta upprört, med skildra vetenskapliga teorier-för vad som är viktigt för det lilla barnet.

Film är ÄR en möjlig underbar fiktion .Förförande.Som boken.Som pjäsen.Som sången.

Att använda som relation.Att bli vän med.

Alla barn visar från början estetiskt starkt intresse.

Så, vad att visa mycket unga?

Alltid det man själv som vuxen tycker är verkligt bra.

Rekommendation: För små och oroliga vuxna.

Tänk om,av teamet regi Linda Hambäck och den rörelse geniala animatören Marika Hejdebäck.Animerade sångsagor, med Nina Persson vackra sång och musik. (Boken Tänk om av Lena Sjöberg) Underbart som film tycker jag ,både gulligt oroande,tjatigt och vackert och överraskande kul.Den berättar lugnt om miraklet livet-ömhet och fara. Den om valarna är nog favoriten den ser jag om och om. Den påminner om min dotter och hennes dotter.Min dotter simmar som en delfin.Hon lärde mig simma när hon var 4 år.Å jag 25.

Omgiven av Capris blå vatten när jag skriver detta,ser jag bildhavet,som vi måste simma och upptäcka tillsammans .

i

-

Konst ska oroa.

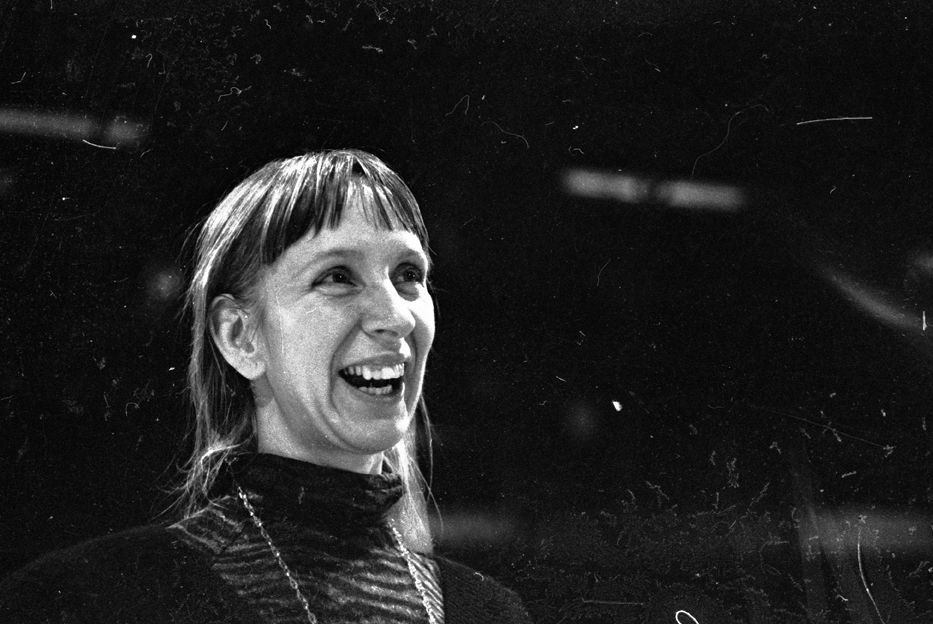

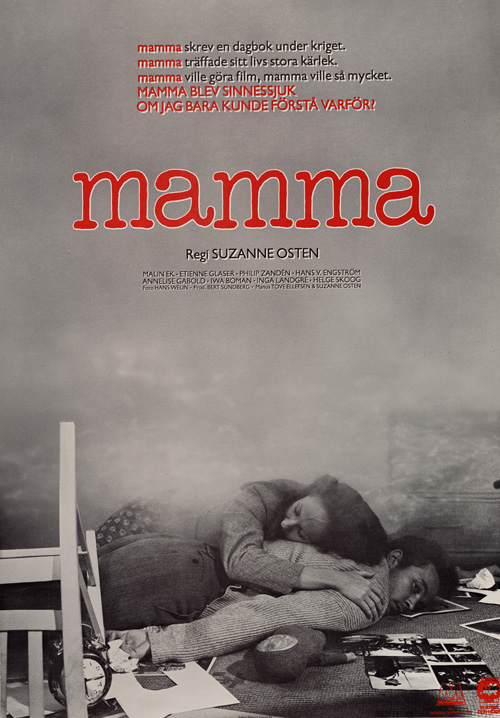

Mamma

En komediantisk historia om en kvinna som vill göra film och inte får det och blir galen.

Min historia lägger sig tätt manusdramaturgiskt nära Woody Allens Manhattan. Ex rytmen mellan bild och dialogscener Och tilltron till dialog på film. Såg mycket film av Renoir och fransk och svensk noir film. Användandet av det inlånade dokumentära startar här. Jag gick på filmkurs i manusskrivning för David Winngate, som lärde oss en del knep, och vad vi förlorar på att undvika den amerikanska dramaturgin. Den store filmregissören Dusan Makavejev tipsade mej om rekvisitans bärande roll .

För att göra sin första film får man vara mycket övertygad. Det blir kanske bara denna? ! Eller ingen om man är kvinna eller 1940 …Tusen åsikter och omarbetningar, tjat om hur film ska se ut eller inte -får inte förstöra nerven och drivet .Trohet mot grundstoryn: här vara kvinna/ filmare/ mor intellektuell i andra världskriget, tema passion. Låta ingen hindra dig! Producentens Bosse Jonssons dåvarande fru tyckte till min fördel: en kvinna skulle få en filmchans.Det är ett rykte! Som 35 åring debutant hade jag ett långt cv laddat med mycket teater och tv och radio och media. Storyn är byggd kring min mors krigsdagbok. Det tog några år få till Mamma, 78-82. Research och partner i skrivandet, Tove Ellefsen. Fotografen Hans Welin(också Bröderna Mozart )och jag gjorde storyboard .Vi klippte.

3 Små filmer av min mamma dök upp, två på nittiotalet, den tredje i 2014.Historien visade sig sann. Det var så att Gerd, min mor,fimkritikern Pavane, ville och kunde filma. men en kvinna DÅ kunde inte få den platsen. Jag ville ta den på 80talet.

-

Låt oss tänka fritt ett tag

Ty vi är ju så rädda. Vi vuxna är rädda om våra barn.Livet är farligt och i dessa tider kryper rädslan för attentat hot och våld närmare.Vi vill ju gärna skydda barnen från det onda. Ibland ingriper vi mot lekar med pistoler, förbjuder ord, hindrar barn att se någon film eller pjäs; vi vill inte skada dem med för sanningsenliga dramer, sanningen om livets oförutsägbarhet. Vi tror oss veta vad som är bäst för barn. Och vi vill roa dem.

Konstens roll

Konstens roll är ju dock att sätta igång oro och frågor.Den goda berättelsen lär oss att uthärda starka känslor och vidga oss för världens mysterium och ta oss vidare med en förstärkt känsla att livet är värt att leva trots faror.Ja du minns att själva faran gör oss levande, vi har enorma krafter. I vår vuxna rädsla vill vi peka på vad barn bör få göra, leka vissa lekar se vissa berättelser.

Men erkänn att vi kontrollerar det de får som berättelser, men inte det barn utsätts för av livet. Våld orättvisor. Oro för Existensen delar vi med de yngsta. Här gäller det tänka högre och friare för oss vuxna, tänka många genrer, breda upplägg av allt möjligt.

Vi behöver inte välja

Det handlar inte om Ipad eller teater. Det gäller inte välja medier som är goda eller onda eller överlägsna.Det kan vara konserter och Tv spel.Barnfilm som är Bambse. Barnfilm kan vara ett koncenptuellt verk om Gamar som sliter sönder ett dukat bord. Moderna Museet har många filmer.Eller själva skapandet, improvisation som lek.Rita storyboard till en film i grupp. Göra film.Bygga lego världar. Det gäller alltså många olika genrer .Låt den unge åskådaren få gå igenom många språk och lösningar.

Som filmambassadör förespråkar jag bara en sak: barn är olika.

Barn behöver fantisera och få reda på hur vi vuxna lever världen fast vi ändå inte tycker vi kan styra den. Det är bara bra, när vi kontrollmänniskor avstår veta allt.

Detta leder till ett utrymme för barns kreativitet- ett hål, det finns sammanhang INTE tänkta ej skapade ej lösta.

Barn behöver skapa både på gamla modeller och få gå till det okända. Men det är guld när vi bidrar med vår lust och passion.Vi måste lära ut alla lnep och finter,läsa film,se reflektera.

Barn behöver välja av allt vi själva tycker är väsentligt och meningsfullt. Men igen:

Barn behöver få hitta även sådant vi vuxna inte gillar , och varnar för,men som har någon konstnärlig ide eller kvalitet.

Jag vill verka för flera konstnärliga uttryck,språk för barnfilmen- som jag i 40 år främjat framväxten av en erkänd teaterkonst för barn i hela värld.